Biofertilizers, as eco-friendly alternatives to chemical fertilizers, play a vital role in sustainable agriculture. In 2026, the production of biofertilizers relies on three core categories of raw materials: biological agents (beneficial microorganisms), nutrient-rich growth media, and carrier materials that maintain microbial viability. These raw materials work synergistically to ensure the activity of beneficial microorganisms from production to application, enabling them to promote plant growth and improve soil health. A clear understanding of these raw materials is essential for grasping the production logic and application value of biofertilizers.

Beneficial microorganisms, also known as biological inoculants, are the core “active” raw materials of biofertilizers, directly determining their functional effects. The main types include nitrogen-fixing bacteria, which can convert atmospheric nitrogen into plant-available forms. This group includes rhizobia (specifically for leguminous plants), azotobacter (free-living in soil), and azospirillum. Phosphorus- and potassium-solubilizing microorganisms are another key category, such as Bacillus megaterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and fungi like Aspergillus niger, which can decompose insoluble phosphorus and potassium in soil into absorbable nutrients. Plant growth-promoting fungi, mainly Trichoderma and mycorrhizal fungi, enhance plant stress resistance and nutrient uptake efficiency. Additionally, cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) like Anabaena and Nostoc are widely used in rice cultivation due to their nitrogen-fixing capacity and adaptability to paddy environments.

Fermentation and growth media are essential for propagating beneficial microorganisms to high concentrations during the production process, providing necessary nutrients and energy. Carbon sources are the primary energy supply for microbial growth, with common raw materials including molasses, sucrose, glucose, and starch, which are easily metabolized by most microorganisms. Nitrogen sources and nutrients support microbial cell synthesis, such as yeast extract, peptone, ammonium salts, and corn steep liquor, which are rich in amino acids and vitamins. Agricultural by-products like rice bran, wheat bran, and various grain husks are also widely used as components of growth media. These by-products not only reduce production costs but also realize resource recycling, aligning with the concept of circular agriculture.

Formulation raw materials, mainly carriers and additives, are mixed with microbial cultures after fermentation to ensure microbial survival during storage and application. Organic carriers are commonly used for their good water-holding capacity and nutrient retention, including peat (a traditional standard carrier, but gradually being replaced due to sustainability concerns), biochar (charcoal), compost, and vermicompost. Agricultural wastes such as bagasse, coffee grounds, filter cake, and cocoa pod husks are also excellent organic carriers, turning waste into valuable resources. Industrial and animal wastes, such as biogas slurry, sewage sludge, and animal manures (cattle, pig, or poultry manure), can be used as carriers after harmless treatment. Mineral-based materials like phosphate rock powder, zeolite, kaolin, and bentonite are selected for their stable chemical properties and porous structures, which protect microorganisms from environmental stress. Additives or protectants include glycerol (to prevent desiccation), gum arabic (for adhesion to plant surfaces), and polymers like alginate or carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) for microbial embedding, extending the shelf life of biofertilizers.

A prominent trend in 2026 is the use of locally available biomass resources (such as molasses, brown sugar, and milk) for on-farm production of biological agents. This approach not only significantly reduces production costs but also promotes the development of a circular bioeconomy by utilizing local agricultural and sideline resources. In summary, the raw materials for biofertilizers are diverse and environmentally friendly, covering biological, nutritional, and formulation categories. The rational selection and matching of these raw materials based on production needs and local resource conditions are crucial for improving the quality and applicability of biofertilizers, advancing the development of sustainable agriculture.

Industrial Integration: Composting Infrastructure for Biofertilizer Production

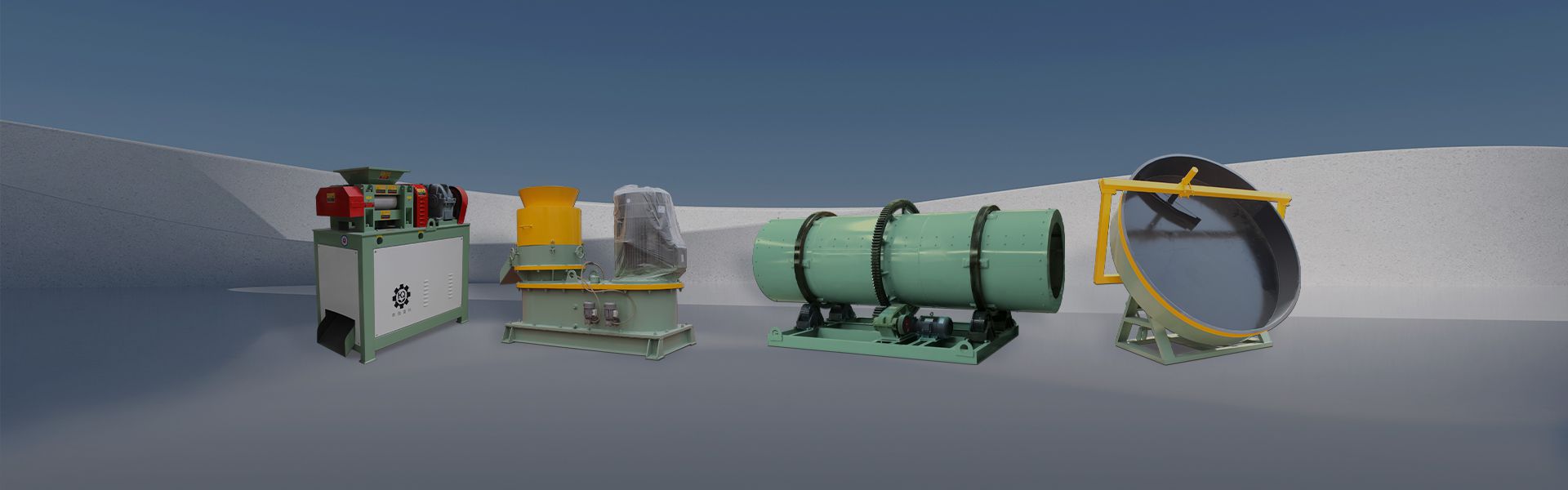

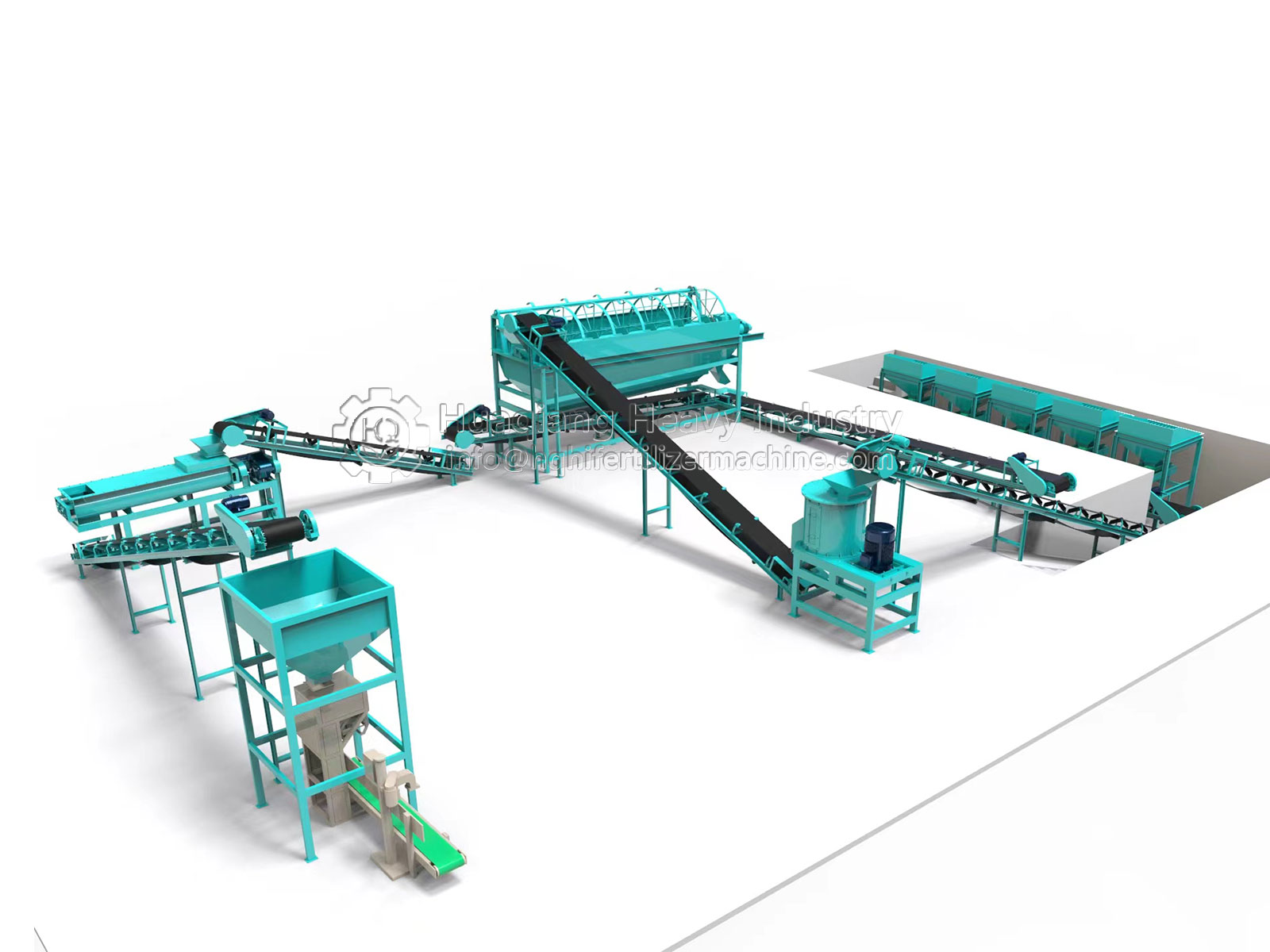

The production of high-quality organic carriers and the processing of agricultural waste feedstocks are foundational steps in the biofertilizer value chain. This is achieved through industrial-scale fermentation composting technology for organic fertilizer. Key equipment in this process includes the large wheel compost turner and the chain compost turning machine, which are essential for aerating and homogenizing windrows in open-air systems. For more controlled and intensive decomposition, trough-type aerobic fermentation composting technology is employed. These machines collectively represent advanced fermentation composting turning technology, transforming raw biomass into a stable, pathogen-free compost that serves as an ideal carrier or base material.

This compost is a critical component of the complete suite of equipments required for biofertilizer production. Following the fermentation stage managed by an agriculture waste compost fermentation machine or a windrow composting machine, the cured compost can be blended with specific microbial inoculants. To produce a market-ready granular product, the mixture is then processed through a disc granulation production line, which shapes the material into uniform pellets without damaging the embedded microorganisms. This integrated system seamlessly connects waste valorization with the creation of a value-added biological product.

Therefore, modern biofertilizer manufacturing is not solely about microbial fermentation; it equally depends on robust upstream composting infrastructure to provide a consistent, high-quality organic matrix that ensures the survival and efficacy of the beneficial microbes from the factory to the field.